It seems that we consciously perceive events exactly as they unfold in time. But that’s probably wrong. Here’s an example.

On the left, a green disk and a red disk are successively presented at the same location for 20 milliseconds each. On the right, the red and green disks are successively presented in different locations. The disks on the right are clearly visible. On the left, however, if the effect works as planned, you don’t perceive the green and red disks, but only a single yellow-ish disk. In this case the effect partly depends on the properties of your screen – it’s better if the disks are equiluminant – so it’s possible that the demonstration above doesn’t work so well for you. In any case, this phenomenon is called “color fusion”, and in proper lab settings, subjects can’t discriminate between the fused green / red disks and a yellow disk.

If we perceived events exactly as they unfold in time, we’d perceive a green disk quickly followed by a red disk. That’s not what we see.

It’s possible to show that the green and red disks are processed in your visual cortex. That’s evidence that you do see them. But it doesn’t feel like it. Why? A reasonable hypothesis is that your brain/mind unconsciously integrates the green and red disks during 40 milliseconds, and then you become conscious of the result of this unconscious processing as a single, integrated yellow disk.

This is an example of a postdictive effect. The presentation of the red disk causes a change in the way you see the green disk, even if the red disk is presented after the green disk. A wide variety of postdictive effects have been documented in the 100 to 150 milliseconds range. The way you consciously perceive something at time t depends on what’s going to happen at time t + 150 milliseconds – approximately the time of an eye blink.

I find these effects fascinating, but they’re not revolutionary. Unless you’re lucky enough to have an immaterial soul doing that job for you, signal processing performed by a material object like the brain has to take some time. As you’re reading this, it already takes approximately 50 or 60 milliseconds for visual signals to go from your retina to your visual cortex. So, I don’t find it so hard to believe that conscious perception can be preceded by 150 milliseconds of unconscious processing.

Some postdictive effects, however, can operate over a longer time range. In a recent article, Herzog, Drissi-Daoudi, and Doerig, review long-lasting postdictive effects in the 350-450 milliseconds range. I’ll talk about some of their main findings here, but I really encourage you to read the article to get the full picture. With Adrien Doerig, we also talked about some of the consequences of this research for theories of consciousness, so if you're interested you can check this article.

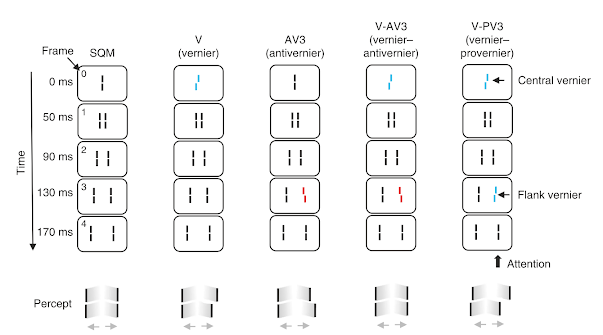

Here’s an example with the “Sequential Metacontrast Masking Paradigm”. This paradigm involves Vernier stimuli (the vertical bars). These stimuli integrate very well when presented one after the other, a bit like the colored disks above. If a Vernier with an offset to the right is followed by a Vernier with an offset to the left (call that an anti-Vernier), what observers report seeing is just a single Vernier with no offset at all (a “neutral Vernier”). This is a postdictive effect: the anti-Vernier changes the appearance of the Vernier even if the former is presented after the latter.

This integration also works when the Verniers appear to move. As illustrated in the figure above (V-PV3), the offset of the first Vernier is “transported” in the stream of Verniers, even if the subsequent Verniers are neutral. Participants just report seeing a Vernier moving to the right, and no neutral Verniers.

Here’s the main finding now. As depicted in the figure above (V-AV3), if a Vernier is followed by neutral Verniers, themselves followed by an anti-Vernier, observers report perceiving a stream of neutral Verniers. It’s a bit as if the anti-Vernier reached back in time to change the way in which the entire stream of Verniers is perceived.

How far back in time? Well, that’s where things get a little crazy… An anti-Vernier can change the way in which the entire stream of Verniers is perceived even if it appears 450 milliseconds after the first Vernier has been presented. This means that the reported appearance of the stream of Verniers depends on what will be presented 450 milliseconds after the stream has started. Yes, you read that correctly. 450 milliseconds. This finding suggests that, at least in this case, there’s a window of 450 milliseconds of unconscious processing before the entire stream is perceived.

This experiment also provides evidence that conscious perception is constituted of discrete episodes, instead of being continuous. But I won’t focus on this aspect here. I won’t focus either on all the other cases of long-lasting postdiction reported by Herzog et al. Instead, let me finish with a short reflection on what this research teaches us about consciousness, and baseball.

Baseball is a game of milliseconds. A fastball thrown at 100mph (161 Km/h) reaches the batter in about 375 milliseconds. If Herzog et al. are right, it takes 400ms for the batter to construct a conscious percept of the ball. Which means that the batter’s conscious visual percept of the ball lags far behind its actual location. In fact, it lags so far behind that the batter hits the ball before she consciously perceives the pitch leaving the pitcher’s hand.

To illustrate a similar – though less extreme – scenario, Nijhawan & Wu (2009) made this great picture:

The white circle represents the hypothetical perceived location of a tennis ball travelling at 60mph, compared to its actual location, assuming a processing latency of just 100 milliseconds. I let you imagine the perceived location of the ball if the latency is actually 400 milliseconds, as Herzog et al. convincingly argue.

That's just unbelievable. I don’t know much about the phenomenology of hitting a 100mph fastball. But my guess is that baseball players don’t feel like they swing the bat before consciously seeing the ball leaving the pitcher’s hand. Instead, they probably feel like they swing the bat at the moment they consciously see the ball approaching towards home plate.

If Herzog et al. are correct, and if that’s indeed how baseball players feel, baseball players are deeply wrong. It’s impossible for them to actually hit the ball at the moment they consciously see it approaching towards home plate. Instead, they unconsciously process the type of pitch the pitcher has thrown, whether it’s going to end up in the strike zone or not, whether they should swing or not, and how. All that, long before they consciously perceive the actual trajectory of the ball.

This leaves us with a puzzle. How can we, baseball players, and Roger Federer of all people, be so wrong? How is it possible that we don’t realize that our conscious experiences can lag 400ms behind reality? I think that two phenomena can independently contribute to the fact that we don’t realize it. Just a caveat before I continue: I’m not an expert on this, so that’s entirely speculative and I’m probably wrong.

First, most of the time the visual world isn’t like an unpredictable stream of Verniers stimuli, and most of us don’t spend our lives guessing what the next pitch is going to be. In ordinary situations, conscious percepts could be constituted before the entire bottom-up visual processing is over, based on predictions of what’s likely to come next. So, your stream of consciousness could “catch-up” with reality if predicting what’s coming requires less processing time than processing incoming sensory information from scratch.

Second, consciousness could be constituted of discrete episodes, and the intuition that the stream of consciousness is a continuous succession of feelings is an illusion. That’s the view held by Herzog et al. I still have a hard time understanding it, even if I’m starting to see the appeal, so I apologize if what comes next is a bit confusing.

Let's start with an analogy. A picture can represent 3-dimensional spatial relations between depicted objects, even if the picture itself only has two dimensions. Just as a picture doesn’t need to be 3-dimensional to represent spatial relations in a 3D space, your experience doesn’t need to be continuous to represent a succession of events. According to Herzog et al.'s view, your experience represents a succession of events, which gives rise to a feeling of succession, even if the experience itself is not constituted by a succession of feelings.

Here’s what actually happens if this view is correct. In the case of the stream of Verniers, for instance, we do not have a succession of experiences – each experience representing a single Vernier in the stream. There’s no succession of feelings. Instead, there’s just a feeling of succession. The entire stream of Verniers is experienced in a single conscious experience with temporal properties assigned to each element of the stream. The fact that elements of the experience are “tagged” with these temporal properties give us a feeling of succession in a single, discrete conscious episode, even if there’s no actual succession of feelings.

According to this view, in between those discrete conscious episodes – which give you the impression that consciousness is continuous, you’re not conscious of anything. We live most of our lives as zombies, unconsciously accumulating information, and reconstructing conscious experiences of what just happened after the facts.

It’s starting to be a bit too vertiginous for my taste, so I’ll stop here. There’s a lot to think about in Herzog et al.’s article. I thank Adrien Doerig for discussing these issues with me, and for reading a previous draft of this blog post.